- Home

- Glenn Frankel

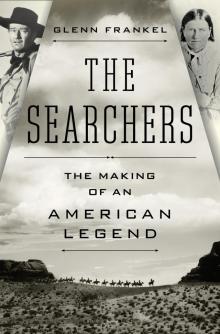

The Searchers

The Searchers Read online

Contents

Introduction: Pappy (Hollywood, 1954)

I

Cynthia Ann

1. The Girl (Parker’s Fort, 1836)

2. The Captives (Comancheria, 1836)

3. The Uncle (Texas, 1837–52)

4. The Rescue (Pease River, 1860)

5. The Prisoner (Texas, 1861–71)

II

Quanah

6. The Warrior (Comancheria, 1865–71)

7. The Surrender (Comancheria, 1874–75)

8. The Go-between (Fort Sill, 1875–86)

9. The Chief (Fort Sill, Oklahoma, 1887–92)

10. Mother and Son (Cache, Oklahoma, 1892–1911)

11. The Legend (Oklahoma and Texas, 1911–52)

III

Alan Lemay

12. The Author (Hollywood, 1952)

13. The Novel (Pacific Palisades, California, 1953)

IV

Pappy and the Duke

14. The Director (Hollywood, 1954)

15. The Actor (Hollywood, 1954)

16. The Production (Hollywood, 1955)

17. The Valley, Part One (Monument Valley, June 1955)

18. The Valley, Part Two (Monument Valley, June–July 1955)

19. The Studio (Hollywood, July–August 1955)

20. The Movie (Hollywood, 1956)

21. The Legacy (Hollywood, 1956–2010)

Epilogue (Quanah, Texas, June 2011)

Acknowledgments

Photograph Credits

Note on Sources

Notes

Bibliography

A Note on the Author

By the Same Author

For Betsyellen Yeager

Everyday

Myths are neither true nor untrue, but the product and process of man’s yearning. As such, they’re the most primal thing bonding us to other people. Yet the phenomenon is much more than a snake feeding on its own tail. Myths gather momentum because they provide hope.

—CYNTHIA BUCHANAN, “COME HOME, JOHN WAYNE, AND SPEAK FOR US”

Introduction

Pappy (Hollywood, 1954)

The most disastrous moment of John Ford’s illustrious Hollywood career took place at the U.S. Navy base on Midway Island in the Pacific Ocean in September 1954. The legendary film director was starting work on Mister Roberts, the movie version of the fabulously successful Broadway play, starring his old friend Henry Fonda. It should have been a great project: directing a comedy about Ford’s beloved Navy with one of his favorite stars, surrounded by his informal stock company of familiar supporting actors and film crew members, with a script by his trusted screenwriter, Frank S. Nugent. What could go wrong?

Almost everything, as it turned out. The biggest problem, surprisingly, was Fonda. Ford had gone to bat for him against the studio executives at Warner Brothers. They had wanted a younger, sexier, and more potent box office attraction like Marlon Brando or William Holden for the title role of Doug Roberts, a young Navy officer consigned to a backwater cargo ship during World War Two and desperate to see combat before the war ends. But Ford had insisted that Fonda, despite being forty-nine, owned the part after playing it to great acclaim for four years on Broadway, and even Jack Warner felt compelled to agree. Fonda was grateful; in a “Dear Pappy” letter he expressed his appreciation that he was working again with the complicated genius who had directed him in Young Mr. Lincoln, Drums Along the Mohawk, The Grapes of Wrath, My Darling Clementine, The Fugitive, and Fort Apache. “It’s so absolutely right that you are going to do the picture,” Fonda gushed.

Nonetheless, from the moment they got to the location, the two men clashed. Fonda didn’t like Nugent’s script, felt it was neither as funny nor as nuanced as the original play, and didn’t care for the excessive physical comedy and coarse broad strokes of Ford’s direction. The Navy opened its gates to the film company: no one in uniform dared to say no to retired admiral John Ford, a decorated World War Two veteran. But on the first day of shooting at Midway, Fonda was disturbed by the way Ford rushed through the scenes and discomfited costar William Powell, who had trouble adjusting to Ford’s swift, one-take-and-let’s-move-on pace. Ford, who dominated his film sets the way Louis XIV presided over the court at Versailles, could not help but notice Fonda’s worried expression.

At the end of the day, producer Leland Hayward arranged for a clear-the-air meeting in Ford’s room in the bachelor officers’ quarters. Ford was sprawled on a chaise longue with a tall drink in his hand. The conversation was short.

“I understand you’re not happy with the work,” said Ford.

Fonda tried to be diplomatic. “Pappy, you know I love you,” Fonda began, and then went on to explain that the play had special meaning for him and Hayward. “It has a purity that we don’t like to see lost. And I’m confessing that I’m not happy with that first scene with Powell.”

Ford had heard enough. Without warning, he sprang from the lounge chair, reared back, and punched Fonda in the face. The actor fell backwards, knocking over a pitcher of water, got up, and fled the room in stunned silence. Fifteen minutes later, Ford knocked on Fonda’s door and stumbled through a tearful, abject apology. Fonda says he accepted on the spot, but things after that were never the same. Ford was a lifelong alcoholic who prided himself on staying sober during a film shoot, but now he started grimly working his way through a case of chilled beer each day on the set. Sometimes, when Ford was too wasted to go on, either Fonda or Ward Bond, another old Ford crony who had a minor role in the picture, finished up the day’s filming.

A few weeks later, soon after the film company returned to Hollywood, Ford was rushed to St. Vincent’s Hospital for emergency gall bladder surgery. Mervyn LeRoy took over and finished the picture. Mister Roberts was a box office hit, and won three Academy Awards, including Jack Lemmon’s first, for best supporting actor. But Ford and Fonda were both bitterly disappointed with the film and with each other. They never worked together again.

John Ford emerged from the Roberts debacle weakened physically and emotionally. He was sixty, a smoker and a drinker, and in poor health. He had had cataract surgery on both eyes a year before, feared he was going blind, and now wore a black patch over his blurred left eye. His beloved older brother Francis was dying of cancer, and the modest but comfortable house on Odin Street where Ford and his wife, Mary, had lived for thirty years and raised their two children was about to be demolished under a city order to help create a parking lot for the new Hollywood Bowl. Even before Mister Roberts, his most recent films had proven to be unsatisfying ventures for him. Even Mogambo (1953), a box-office hit starring Clark Gable, Ava Gardner, and Grace Kelly, left him worn-out and frustrated with the studio, the actors, and his own flagging health. Ford’s world—which he had carefully organized to serve his immense personal needs and protect him from those outside forces he could not control—seemed to be caving in. “It was clear,” wrote Maureen O’Hara, another of the recurring cast of actors who both worshipped and feared him, “that John Ford was going through changes and that they were terrible ones.”

Still, Ford wasn’t finished. As he tried to put back together the pieces of his damaged career following the humiliation of Mister Roberts, he turned to what he knew and loved best.

The Western had been John Ford’s favorite movie genre ever since he first arrived in Hollywood forty years earlier in the formative days of moving pictures, and he had made nearly fifty Westerns during the course of his career. There was something about a man riding a horse through the rugged landscape, Ford liked to say, that made it the most natural subject for a movie camera. He loved telling stories of cowboys and Indians and cavalrymen, and he loved taking his company of actors, cameramen, wranglers, and stuntmen on location to Monument Valley alo

ng the Utah-Arizona border, famous for its scenic beauty and its utter remoteness, far from the reach of the studio money men and their regiments of sycophantic retainers. There he would harangue and abuse his loyal crew, bend them to his will, and inspire them to do their finest work. And he loved working with John Wayne, his favorite actor and occasional whipping boy. Under Ford’s demanding and meticulous direction, Wayne had become America’s most iconic Western star: the solitary, taciturn man on horseback, true to his own code and adept with his fists and his guns. They were like father and son, wise old mentor and humble pupil, with Wayne in the subordinate role even after he became the country’s top box-office attraction.

John Ford at Monument Valley, June 1955, during The Searchers film shoot.

No surprise, then, that Ford once introduced himself to a roomful of fellow directors by declaring, “My name is John Ford and I make Westerns.” The genre was at the core of his identity.

And now, at the moment of Ford’s greatest need, his longtime friend and business partner, Merian C. Cooper, came up with the idea for a Western he thought John Ford would find irresistible.

THE SEARCHERS, a new novel by the author and screenwriter Alan LeMay, was a captivity narrative set in Texas during pioneer days, and it was rich with strong characters, dramatic scenes, and an undercurrent of sexual obsession. It was based in part on a true story: the abduction of a nine-year-old girl in eastern Texas in 1836 by Comanche raiders who slaughtered her father, grandfather, and uncle, and kidnapped her and four other young people. Cynthia Ann Parker had been raised by her captors and became the wife of a Comanche warrior and mother of three. James Parker, her uncle, a backwoodsman and devout Baptist who possessed a dubious set of morals and an abiding hatred for Indians, searched eight years for her and her fellow captives—one of them his own daughter Rachel—and helped recover four of the missing.

But not Cynthia Ann. She lived with the Comanches for twenty-four years, until she was recaptured in 1860 by the U.S. Cavalry and Texas Rangers in another murderous raid and restored to her white relatives. Kept apart from her Comanche family, she died in misery and obscurity. But her surviving son, Quanah, became one of the last great warriors and later on an apostle of reconciliation, helping preserve the remnants of the Comanche nation and invoking the spirit of his dead mother to preach peace and understanding between whites and Native Americans. The two sides of the Parker family—one of them Texan, the other Comanche—still honored the legacy of their distant ancestors at family reunions and had even begun sending emissaries to each other’s events.

The story of Cynthia Ann Parker had been told and retold, altered and reimagined, by each generation to fit its own needs and sensibility, until fact and fiction had blended together to form a foundational American myth about the winning of the West. Cynthia Ann, in the version published and passed down by Texas historians, became a romantic and tragic figure, rescued from savages but doomed to unhappiness because the barbarians had corrupted her soul by subjecting her to a fate worse than death: sexual relations with Indians. Her half-white son was the Noble Savage who led his childlike people down the path to civilization. There were other accounts, compiled mostly by female relatives, that paint a sadder and more complex portrait of mother and son. But those accounts were never published and remain scattered and un-annotated in the American History archives at the University of Texas at Austin.

The legend gave rise to a prairie opera, one-act plays, fanciful narratives, and fables—and in 1954 to Alan LeMay’s powerful novel, one of the best Westerns of its era. LeMay moved the original story forward some thirty years to the late 1860s, when Comanche power was waning, added elements from other captivity narratives he had compiled, and turned the focus from the female captive to two relatives—her uncle and her adopted brother—who spend seven years searching for her.

Ford, a voracious reader who was steeped in the history of the American West, had once commissioned a screenplay about Quanah for a film that never got made. Now he read LeMay’s novel and saw its cinematic possibilities. Ford had Cooper quickly arrange for Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney, a scion of two massive family fortunes who was looking to get into the movie business, to acquire the screen rights on his behalf. Leveraging Whitney’s money, Cooper made a deal with Warner Brothers for additional financing and distribution rights, and Ford and his crew set out for Monument Valley.

The movie Ford sought to make had all the elements of the classic Western—a harsh and stunningly beautiful setting, hardy settlers, stoic pioneer women, brutal and rapacious Indians, and a hard, relentless protagonist who stalks the frontier like an angry lion on a mission of vengeance. It was, as the publicity posters proclaimed, “THE BIGGEST, ROUGHEST, TOUGHEST … AND MOST BEAUTIFUL PICTURE EVER MADE!” But Ford also celebrated the frontier community and its rituals—its weddings, family meals, square dances, and funerals—the coming together of hardworking people to share their triumphs and humor and mourn their losses. The Searchers was not just an adventure story but a parable about the conquest of the American frontier.

But while The Searchers pays homage to the familiar themes of the classic Western, it also undermines them. Its central character possesses all of the manly virtues and dark charisma of the Western hero yet is tainted by racism and crazed by revenge, his quest fueled by hatred. His goal is not to restore his lost niece to the remnants of their broken family but to kill her, because she has grown into a young woman and has become a Comanche bride and, willingly or not, has had sex with Indians. He is bent on enforcing sexual and racial purity by performing an honor killing as twisted and remorseless as any carried out in the medieval recesses of the Middle East.

Ford was a storyteller who loved to create and manipulate myths, and as he grew older and more complex, he loved to challenge them as well, reaffirming the audience’s deepest conventional wisdom and then gently shattering it. Despite all of his personal setbacks, he rose to the height of his creative powers in The Searchers. He is responsible for the film’s visual poetry—its skill in moving from the intimacy of domestic interiors and family life to the terrible beauty of the gothic sandstone cathedrals and vast, obliterating plains of Monument Valley—as well as its deep and passionate emotions.

At the heart of The Searchers is John Wayne’s towering performance as Ethan Edwards. Despite his reputation for knowing how to play only the righteous hero, Wayne had portrayed morally ambiguous men before, most notably the autocratic trail boss in Red River (1948) and the brutish Marine sergeant in Sands of Iwo Jima (1949). But in The Searchers he is darker, angrier, and more troubled than ever. This dark knight is determined to exterminate the damsel and anyone who stands in his way. He shoots the eyes out of a Comanche Indian corpse, scalps another dead Indian, disrupts a funeral service, fires at warriors collecting their dead and wounded from the battlefield, and slaughters a buffalo herd to deprive Comanche families of food for the winter. Still, because he is played by John Wayne, we identify with Ethan’s quest even as we recoil from his purpose. His charisma draws us in, making us complicit in his terrible vendetta.

“Wayne is plainly Ahab,” writes the cultural critic Greil Marcus. “He is the good American hero driving himself past all known limits and into madness, his commitment to honor and decency burned down to a core of vengeance.”

Largely overlooked in its time—it was not nominated for a single Academy Award—The Searchers has become recognized as one of the greatest of Hollywood movies. It was extraordinarily influential on a generation of modern American filmmakers—from Steven Spielberg to George Lucas to Martin Scorsese—imprinting itself on their psyches and their ambitions during their formative years. “It was a sacred feeling,” recalled Scorsese, who first saw the film at age thirteen, “seeing that movie on that big screen.” The film was also the forerunner of the postmodern wave of introspective Westerns—from Ford’s own The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) to Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969) to Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven (1992)—

that dissect the values and assumptions of the genre even while honoring them. Just as Ernest Hemingway noted that “all modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn,” film critic Stuart Byron once declared, “in the same broad sense it can be said that all recent American cinema derives from John Ford’s The Searchers.”

Like Spielberg, Lucas, and Scorsese, I, too, was entranced by The Searchers as a boy coming of age in the 1960s. Everything about it thrilled and frightened me. Wayne’s command of the screen, his terrifying anger, and his unpredictable blend of affection and derision toward his young nephew and fellow Searcher, played by Jeffrey Hunter, at times reminded me of my own father. There was dust and grit in every scene, and even the gunshot sounds seemed sharper and more real than in other Westerns. And the climactic moment when the uncle chases down his niece and must decide whether to wreak his terrible revenge made me weep with fear and pleasure.

But what entranced me most were the Comanches. They make only a few appearances in the film, yet they are the psychological terror in the night that haunts the white settlers, and they haunted me as well. Ford’s portrait of them is mostly one-dimensional: Indians in The Searchers are for the most part murderers and rapists, and some critics have accused the film of practicing the same racism it purports to condemn. Yet Ford also grants Indians their humanity: the evil war chief Scar justifies his campaign of murder and abduction as revenge for the killing of his own two sons by whites. The aftermaths of two massacres are depicted in the film, with the burning farmhouse where a pioneer family has been slaughtered in the first act of the story balanced later by a burning Indian village strewn with the corpses of men, women, and children mowed down by soldiers. And even as a boy I could see that when Ethan Edwards finally confronts Scar, the two warriors share a mutual hatred that binds them in a fatal embrace.

I grew up to become a journalist, and my travels as foreign correspondent for the Washington Post took me to the Middle East and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Like the Plains Indian wars, this, too, was an intimate war of populations in which women and children were both victims and participants. Each side saw the struggle, in Kipling’s imperial phrase, as a “Savage War of Peace” in which only one could triumph and the loser must be exterminated physically or culturally or both.

The Searchers

The Searchers